Blog Post #28

*Dear Friends, I am pleased to share this article written for a recent issue of The Mogul Muse Magazine, of which I am currently Writer-in-Residence.

“You can fly, but that cocoon has to go!” – Mary Ellen Edmunds

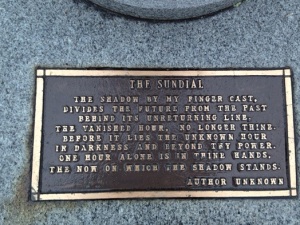

There is a word feared and avoided more than most in the English language. It threatens, it cajoles, it looms, it surprises. It induces stress and heightens anxiety. It is both menacing and nurturing. Innocent in its intentions, it is the standard-bearer of growth. In most cases, innocuous, it can brighten one’s perspective, act as a harbinger of hope, and create anticipation and excitement, yet in the same breath, it may grip one with fear. What is this simple word? It ischange.

Why does change create so many diverse and emotionally charged reactions? I believe, by its very nature, it suggests the unknown. Let’s face it—the unknown can be unnerving. Especially when change creates unknowns in things close to one’s heart—one’s being, one’s thinking, one’s relationships, or one’s way of life.

Change is like that. In a moment, the Unknown may rear its precipitous head, and normal life goes topsy-turvy—a layoff, an accident, a death. But in all fairness, change doesn’t necessarily denote something bad. It can also bring happy surprises. A new baby, for example—one moment, in mother’s womb, the next, cuddled and adored by the whole family. (The household still turned upside down, but the repercussions are, for the most part, positive.)

Here are a few possible examples of positive change: a new job, a wedding, a new home, or a move.

Now, consider if you will, a few possible examples of negative change: a new job, a wedding, a new home, or a move.

The power of change as a force for good or ill depends largely on how we choose to view it.

Interestingly, it is the nature of change to be unsettling, even in the best of times. Clinging to the apron strings of any kind of major change are tinier seeds of change that potentially produce positive or negative results, or both. A new job may bring better pay, but longer hours and more stress. A wedding brings blissful joys at the same time generating expenses, difficult decisions, and perhaps stirring up familial issues. A new home may mean a fresh start, more room, or better location, but it may also mean leaving an old home, changing schools, and leaving friends behind. A move is, at best, stressful, but may open up a variety of new opportunities.

Like foxtails that work their way into the fabric of life, tiny seeds of change riding on the backs of greater changes poke and prickle until one takes notice. For example, an injury may carry with it foxtails of fear and uncertainty about one’s future, as well as cockleburs of faith and determination. The injured may choose complete debilitation by cultivating the seeds of fear, or he or she may choose nurturing faith over despair, engendering newfound strengths and the ability to inspire others. In choosing to nurture the good or the bad seed, a transformation will occur. Plucking out the annoyance, while planting and nourishing the good seeds of change, will over time, transform those seedlings as they grow into good fruit. Neglecting potentially good seed, while allowing bad seeds to fester, will eventually cause bitterness and further tribulation.

Changing oneself is the most disconcerting transformation of all. Purposely seeking to change aspects of oneself may mean recognizing an inherent quality that is unhealthy, destructive, or unworthy. On the other hand, it may mean cultivating positive attributes that are underdeveloped. In purposeful transformation, change may itself appear to be “the bad guy” (it’s difficult, it nags, it’s demanding). But after effecting change, “the good guy” emerges (it got easier, I no longer need reminders, I triumphed). The fruit of change then appears and validates with improved health, healthier relationships, increased gifts and talents, peace, hope, and shared joy.

Some seek change for the wrong reasons, such as to fit someone else’s standard or ideal of beauty, or to feel a part of a group, cult, or clique. While it may be advantages to conform to higher standards of morality and appearance related to a worthy institution or belief system, to seek to lower one’s true nature for the sake of popularity or acceptance is self-deceptive and may very well be self-destructive.

A classic example of transformation is represented by the life cycle of a butterfly. At first, a caterpillar eats and eats and eats, preparing for the pending change of circumstance. Once it builds its chrysalis, it fearlessly faces the unknown—it doesn’t know exactly what it will become, or what the process of “becoming” will be like, but it is committed to fulfilling its mission. Consequently, it is bound-up in a tight spot of its own making for a while. I suspect it is cramped and uncomfortable, and endures growing pains during the process of transformation. At last, it emerges, a new being, with a new demeanor and wardrobe, and a new means of transportation. No longer will the caterpillar be forced to creep and crawl, but will now have wings to flit and flutter about the garden.

Does the butterfly fret and stew over the chrysalis? Does it drag it along wherever it goes? Does it cling to its old ways of doing things, crawling instead of flying? The answer is an emphatic NO!

Indeed, the butterfly embraces the change in its entirety. It moves forward with a sense of mission and purpose. It is fulfilling the measure of its creation, and by so doing has and gives joy.

Transformation may be rooted in our thinking and belief systems. If we believe change is good, or that we can or should change for the better, then we stand a better chance of effecting positive results. If we believe there’s no point to change, and that we can’t change, we will essentially remain stagnant.

Consider the following two versions of a wonderful fable of transformation, each having a different result.

1 – The Eagle Who Thought He Was a Chicken:

A baby eagle became orphaned. He glided down to the ground from his nest but was not yet able to fly. A man picked him up. The man took him to a farmer and said, “This is a special kind of barnyard chicken that will grow up big.” The farmer said, “Don’t look like no barnyard chicken to me.” “Oh yes, it is. You will be glad to own it.” The farmer took the baby eagle and placed it with his chickens.

The baby eagle learned to imitate the chickens. He could scratch the ground for grubs and worms too. He grew up thinking he was a chicken.

Then one day an eagle flew over the barnyard. The eagle looked up and wondered, “What kind of animal is that? How graceful, powerful, and free it is.” Then he asked another chicken, “What is that?” The chicken replied, “Oh, that is an eagle. But don’t worry yourself about that. You will never be able to fly like that.”

And the eagle went back to scratching the ground. He continued to behave like the chicken he thought he was. Finally he died, never knowing the grand life that could have been his.

When an eagle was very small, he fell from the safety of his nest. A chicken farmer found the eagle, brought him to the farm, and raised him in a chicken coop among his many chickens. The eagle grew up doing what chickens do, living like a chicken, and believing he was a chicken.

A naturalist came to the chicken farm to see if what he had heard about an eagle acting like a chicken was really true. He knew that an eagle is king of the sky. He was surprised to see the eagle strutting around the chicken coop, pecking at the ground, and acting very much like a chicken. The farmer explained to the naturalist that this bird was no longer an eagle. He was now a chicken because he had been trained to be a chicken and he believed that he was a chicken.

The naturalist knew there was more to this great bird than his actions showed as he “pretended” to be a chicken. He was born an eagle and had the heart of an eagle, and nothing could change that. The man lifted the eagle onto the fence surrounding the chicken coop and said, “Eagle, thou art an eagle. Stretch forth thy wings and fly.” The eagle moved slightly, only to look at the man; then he glanced down at his home among the chickens in the chicken coop where he was comfortable. He jumped off the fence and continued doing what chickens do. The farmer was satisfied. “I told you it was a chicken,” he said.

The naturalist returned the next day and tried again to convince the farmer and the eagle that the eagle was born for something greater. He took the eagle to the top of the farmhouse and spoke to him: “Eagle, thou art an eagle. Thou dost belong to the sky and not to the earth. Stretch forth thy wings and fly.” The large bird looked at the man, then again down into the chicken coop. He jumped from the man’s arm onto the roof of the farmhouse.

Knowing what eagles are really about, the naturalist asked the farmer to let him try one more time. He would return the next day and prove that this bird was an eagle. The farmer, convinced otherwise, said, “It is a chicken.”

The naturalist returned the next morning to the chicken farm and took the eagle and the farmer some distance away to the foot of a high mountain. They could not see the farm nor the chicken coop from this new setting. The man held the eagle on his arm and pointed high into the sky where the bright sun was beckoning above. He spoke: “Eagle, thou art an eagle! Thou dost belong to the sky and not to the earth. Stretch forth thy wings and fly.” This time the eagle stared skyward into the bright sun, straightened his large body, and stretched his massive wings. His wings moved, slowly at first, then surely and powerfully. With the mighty screech of an eagle, he flew.

Both stories are from Walk Tall, You’re A Daughter Of God, by Jamie Glenn

Truly, you are not caterpillars. You are not chickens. Figuratively speaking, you are butterflies and eagles. Embrace worthy transformation….

Fly!

~~~~~~~~~~~

From the bottom of my heart, I thank you, dear friends, for reading.

Tweet